Mussels from different parts of world share similar crystal orientation in shells

News, 24 July 2025

Scientists of the Laboratory of Neutron Physics at JINR and the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (PIN RAS) compared the crystallographic texture of the shells of Mytilus bivalves (mussels): Bathymodiolus thermophilus, which lives at a depth of about 2500 m at a distance from the coast of Chile and Peru in the Pacific Ocean, and their relatives, Black Sea mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), along with other representatives of the genus Mytilus, which vacationers can collect right on beaches.

Despite the significant differences in the lifestyle of these molluscs, the texture of minerals in their shells turned out to be practically the same and is highly likely to be a stable feature of the entire family. In addition, the crystallographic texture of B. thermophilus was measured with high accuracy in the entire sample volume for the first time. The study will help better understand the mechanisms of biomineralisation and the formation of mineral skeletons by living organisms. In the long term, the development of this research area may lead to the creation of organic matrix materials with specified properties.

Samples of the studied mollusc shells: B. thermophilus (top) and M. galloprovincialis (bottom). The red rectangle indicates the fragments for studying the microstructure.

Samples of the studied mollusc shells: B. thermophilus (top) and M. galloprovincialis (bottom). The red rectangle indicates the fragments for studying the microstructure.

The mollusc shells were taken from the waters of the Sea of Azov in Crimea, the shores of the Adriatic Sea, the North Sea, the Black Sea coast of Romania, the Aleutian Islands, and South Africa. B. thermophilus deep-sea molluscs were provided for research by the employees of the RAS Shirshov Institute of Oceanology. The Institute of Oceanology is actively studying communities of organisms living in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. Samples of Bathymodiolus shells were collected during the 2003 expedition at a depth of about 2470 m, in the area of 9°50’ N 104° 17’ W, where hot springs of the mid-ocean ridge, the East Pacific Rise, come out on the boundary of tectonic plates.

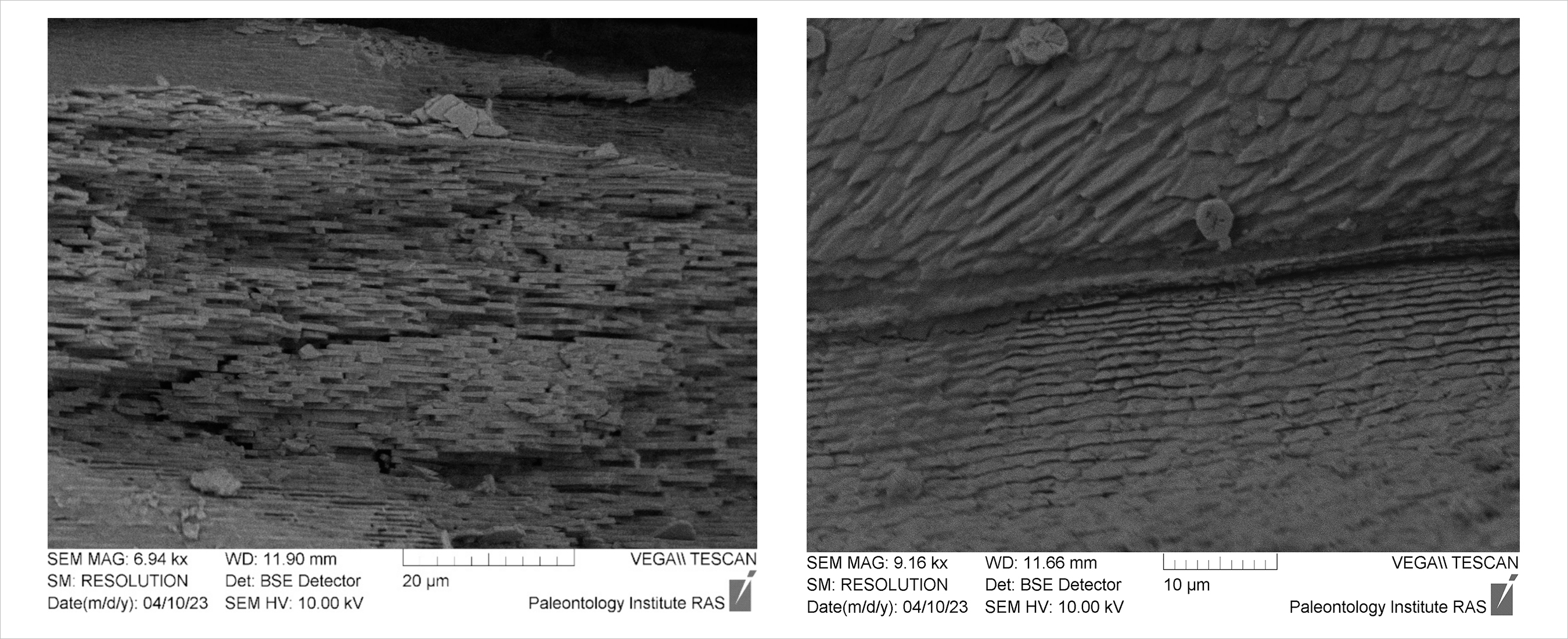

The temperature of the streams is several tens of degrees; meanwhile, in areas with no hot springs, the water temperature is close to zero. Therefore, deep-sea mussels near springs live at + 20-30 °C, almost the same as Black Sea mussels in shallow water. But their environmental conditions are completely different, they are extreme: daylight does not reach such a depth, because of the high pressure of about 250 atmospheres. And most importantly, the mineral composition of the water at the outlet of the springs is completely different from the others, as it contains large amounts of hydrogen sulfide and a lot of compounds of various metals: iron, zinc, manganese, copper, etc. “Accordingly, the acidity of the water there is increased, and during acidification, calcium carbonate, which makes up the calcite and aragonite minerals, of which the shell valves consist, has to dissolve or change somehow. We assumed that both the microstructure and the crystallographic texture of this mineral may differ in deep-sea and shallow-water mussels,” co-author of the study, a FLNP JINR and PIN RAS senior researcher Alexey Pakhnevich explained. The microstructure of the shells of all the studied molluscs turned out to be similar, with the only difference being the shape of B. thermophilus fibres.

Microstructure of B. thermophilus (left) and microstructure of M. galloprovincialis (right)

Microstructure of B. thermophilus (left) and microstructure of M. galloprovincialis (right)

The crystallographic texture – the predominant crystal lattice orientation in a polycrystal in relation to external planes and directions – was measured not on one valve, but on several, since there may be an anomaly in one particular valve if the mollusc was sick, ate sparsely, or lived in cramped conditions during its lifetime.

The position of the sample from the shell of B. thermophilus in the SKAT Diffractometer. XYZ is the coordinate system, where the Y axis is the direction of the predominant trajectory of the growth of the shell

The position of the sample from the shell of B. thermophilus in the SKAT Diffractometer. XYZ is the coordinate system, where the Y axis is the direction of the predominant trajectory of the growth of the shell

“When we measured a few valves, it seemed that the texture was almost the same as that of Black Sea mussels. That is, extreme conditions – pressure, water acidification, chemical properties – do not affect the texture. This is the first important conclusion,” Alexey Pakhnevich emphasised.

The studied deep-sea and ordinary molluscs belong to two different subfamilies of the mussel family (Mytilidae). The similarity of the orientation of the crystallites in their valves indicates that the texture can serve as an important taxonomic feature, proving that the biological organisms belong to the same group, or, in this case, the same family.

This is not the first study by a scientific group that shows that the crystallographic texture is a very stable characteristic of living organisms’ shells. Previously, researchers had already compared the same species of Black Sea mussels M. galloprovincialis at different time periods: modern ones from the Sea of Azov and fossils that were about 30 000 years old. The crystallographic texture of both turned out to be generally the same as well (the calcite texture in fossils is slightly sharper than in modern ones).

“It seems that if such different living conditions lead to the same texture, it means that it is somehow optimal. It would be interesting to understand what makes it so stable. Evolution discards what is weak or not prepared for the external conditions. Since these mussels survive in such different conditions, it means that their texture is evolutionarily very beneficial,” co–author of the study and a FLNP JINR senior researcher Dmitry Nikolayev concludes. Scientists have yet to figure out its exact benefits. Perhaps this texture makes shells more durable, allows for faster growth of the mussel, or gives it the opportunity to consume fewer nutrients.

The crystallographic texture of the valves was measured by neutron diffraction at the SKAT (spectrometer for quantitative analysis of texture) Facility of the IBR-2 Research Reactor.

In the summer of 2024, a scientific expedition took place on the banks of the Volga River in the Saratov and Volgograd Regions. The marine sediments of the Upper Cretaceous epoch (100.5–66 million years old) come to the surface here. Based on the results of this trip, researchers plan to measure the crystallographic texture of minerals in the shells of Amphydonta bivalve molluscs and in belemnite rostrums (known in Russia as “Devil’s finger”).

The site of the expedition on the banks of the Volga River in the Saratov and VolgogradRegions is the Coast of the Plesiosaurs

The site of the expedition on the banks of the Volga River in the Saratov and VolgogradRegions is the Coast of the Plesiosaurs

Near Serpukhov (Moscow Region), a scientific group collected stromatolites, the fossil remains of the waste products of ancient cyanobacteria communities. The texture of this material, in which calcium carbonate is replaced by silicon oxide, will be compared with the texture of the surrounding rock and with stromatolites from other locations. “Even after the death of cyanobacteria, stromatolite still remains a biological matrix. And substitute minerals, the texture of which differs from ordinary silicon, grow along it,” Alexey Pakhnevich commented.

In addition, samples were collected in Crimea of the closest extinct relatives of the fossil molluscs Gryphaea dilatata studied by a scientific group in 2022. “Our goal was to find molluscs from the same family, but from a different geological period, in order to compare them. This area of research concerns changes in the crystallographic texture over time, its stability and permanence,” Alexey Pakhnevich added.

The Far East Geological Institute of the RAS Far Eastern Branch expressed interest in the studies of the scientific team. Colleagues from the Far East plan to provide researchers with shells of the local mussel of the genus Modiolus to study their crystallographic texture.