Science is a leap into future

Interview, 06 December 2018

An interview with First Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education, Academician G. V. Trubnikov, published in No. 11, 2018 of the journal “V mire nauki”*.

*In scientific world

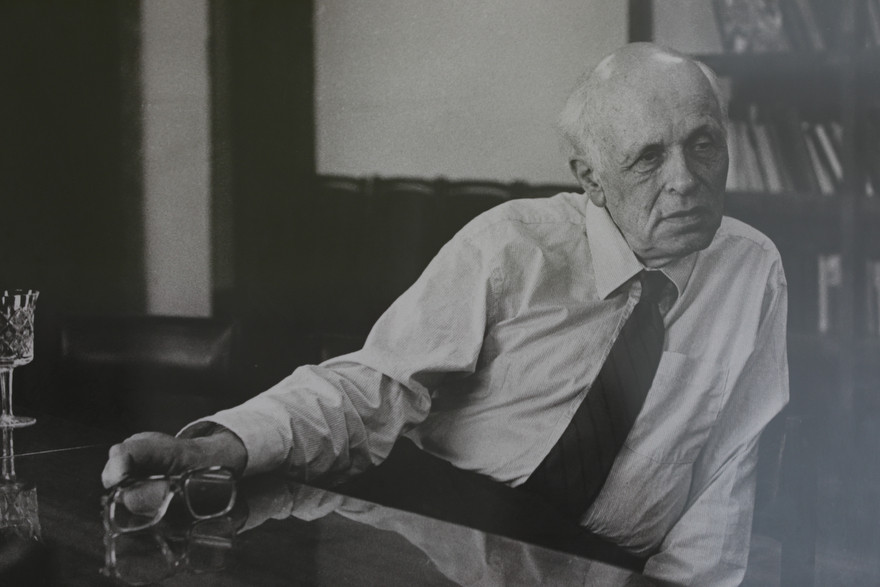

The interview with G. V. Trubnikov is published on the Scientific Russia website. A video version of the conversation is also available there. The interview was conducted by Vladimir Gubarev, photos by Nikolay Malakhin.

- Ensuring that the Russian Federation is among the world’s top five countries in priority directions of scientific and technological development.

- The attractiveness of the Russian Federation for the world’s leading scientists and young researchers to work there.

- Outpacing research development funding from all financial sources compared to the growth of national income.

- Establish of an advanced research infrastructure.

- Upgrade the instrument base by at least 50%.

- Create world-class scientific centres, including a network of international mathematical centres.

- Develop 15 world-class science and education centres based on the integration of universities and scientific organizations of the real sector of the economy.

- Establish training and growth centres for scientific and pedagogical personnel.

This is how I began my conversation with the First Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education, Academician G. V. Trubnikov:

— Is the Science project crazy enough to be implemented? Please, answer as a scientist and as an official. By the way, are you more of a scientist or an official today?

— An expert and a scientist, I dare hope. However, scientists should not only deal with formulas and their research, but also, as a member of a professionally qualified community, be responsible for a particular area of society they represent. It depends on both generosity of spirit and self-esteem. Therefore, a good scientist could potentially be the right official. And an official involved in science policy, I think, should also be a scientist and an expert, because one is obliged to understand what one is trying to modernise, reform, destroy, or create.

— Now I understand why you have a portrait of A. D. Sakharov. One of his ideas is to engage scientists into power: it is they who should lead the society. So you implement his ideas? What do you like about Andrei Dmitrievich?

— A lot. I would only disagree with your thesis that I implement his ideas, because I can’t even put myself next to him. He was, after all, a scientist, a citizen, a politician, and a public figure on a very wide scale. If I am good at something other than what I think I am good at, that’s good.

— Is he close to your spirit?

— Absolutely. Firstly, he is a role model for so many scientists particularly as a theoretical physicist who achieved absolutely fantastic results. Secondly, he exemplifies a certain firmness of belief. This is also important in science, because science is a search for truth. There are many temptations along the way, and the man is weak. And it is important for any scientist to doubt the result he or she has obtained, to believe, but to doubt. This is also important in the area of governance. I don’t really like the word official, but for them to be tenacious and determined in achieving a certain position is also important.

— I think that the office where we are talking had two very prominent scientists working in, N.P. Laverov and G.I. Marchuk. Both of them, I was lucky enough to talk to them, believed that a scientist must also be an official (they said an organizer) in order for science to develop successfully. Has that spirit survived to this day?

— I don’t know, unfortunately, exactly which office they were sitting in, but there is a certain spirit in the building. It was built in 1948. In Moscow, destroyed after the war, it was one of the first buildings that became a symbol not only of the reborn and triumphant nation, but also of the state priority. It is located in the main street, with a view of the Kremlin. It was a symbolic move by the government to have science nestled here, and it was absolutely the right thing to do.

— And nearby thetr is a house with commemorative plaques on its facade listing the names of our great scientists.

— I very well remember the first time I came to this building. It was in 2006. I defended my PhD in 2005 and applied for a presidential grant for young candidates. There was a very serious competition at the time, and I managed to be one of the winners. I had to bring the documents to the Ministry’s expedition, which was located in this building where we are talking to you now. I left the underpass, walked past the building at 9, Tverskaya Street and read: A. A. Bochvar, Y. B. Khariton, I. I. Artobolevsky, K. I. Skryabin lived and worked here… Legends! I walked along and realised that the atmosphere in this place is special, fantastic. And now I work here.

— Since you said the word “fantastic”, let’s go back to the notion of “fantasy in blueprints”, as S.P. Korolev once said. Can you say that about the Science project, the creation of which you were involved in?

— The project implies a team, and it is certainly not a construction blueprint. Interestingly, you mentioned S.P. Korolev… I took my kids to VDNH yesterday. We left the underground and walked through the Cosmos park. I recently read to them about K. E. Tsiolkovsky. And there was a monument to him. And so we saw an absolutely wonderful monument to S. P. Korolev, depicted in motion, in gust. I told my children who S. P. Korolev was and what he did. Told about the cosmonauts – Yu. A. Gagarin, V. V. Tereshkova, A. A. Leonov, V. M. Komarov…

— And so I appear with a reminder of S. P. Korolev. But we are standing on the shoulders of giants, as Newton said, and so a throwback to the past is natural and understandable.

— We present so far a draft outline of the national project Science, passport of the project. We show it as we see it from the side of the Ministry, where there are people who also have some scientific experience. We have to present an adequate document, which will be an instrument of the president’s strategy and decree. It is important to link this project with other national projects. It is impossible to develop science in isolation from crucial areas such as healthcare, demography, agriculture, transport infrastructure, etc. And we presented the passport of the national project, its “skeleton”, to the RAS Presidium, at several major forums, as a team of three Deputy Ministers. We visit the venues of leading universities and various round tables. The process of getting feedback from the professional community is now underway – the skeleton becomes covered with muscles and tendons. Internal organs appear — the heart with the vascular system, the digestion, etc.

— What is the Academy of Sciences, the heart or the brain?

— I think both. The Academy, the Ministry, universities, and the high—tech industry are now the main players in this national project. I think we are finally moving towards a good balance of higher education, university, and academic science.

— Finally!

— A balance of higher education, academic and sectoral science is one of the main goals of this national project. When it is realised, there will be a complementarity of the three components. The country still has quite a serious sectoral science. It is not developed everywhere because of the economic and social transformation that has taken place in the country over the last 25 years, but this situation must be rectified. “The science triangle”, consisting of science, higher education, and industry, in this national project should be a powerful engine and provide the energy for the country’s development.

— Don’t you think you should first choose a goal before looking for ways to achieve it? It was this way in the history of the country: the GOELRO plan, industrialisation, the atomic and space projects… Various structures were formed for them. Two great achievements in 1957 included the first artificial satellite and the launch of the Synchrophasotron in Dubna. It was these two events that largely ensured the successful development of our science.

— Yes, V.I. Veksler’s Synchrophasotron, then A.M. Baldin’s Nuclotron, a unique superconducting machine.

— And now NICA, which is the new accelerator machine. That is, the goal comes first, followed by scientific research. What is the ultimate objective now?

— The objectives are formulated in a presidential decree. We need to have an advanced research infrastructure. We are talking about a radical renewal and modernisation of the entire country’s instrument base.

— This will require a huge amount of money.

— Yes, it takes a lot of resources. We need to support the strong ones and find a place for those who are not in the first cohort, to use the best of what they can for the sake of the main priorities. The second objective is to make the field of science and technology in Russia attractive. We want to increase the number of researchers in Russia by about 100,000. Given that the demographic trend is, frankly speaking, not brilliant, plus the serious competition for talented researchers from other countries, it is not easy to do so. This is only possible by setting serious ambitious world-class tasks and providing the right conditions to work on such tasks. I want to emphasise that it is the research task that is primary. It is attractive if ambitious, and this is the most important thing for a scientist. The second is the toolkit, i.e. the conditions for conducting research: accessibility, openness, mobility, etc. The third is the infrastructure and social conditions.

Addressing these three challenges is very non-trivial, especially in today’s world, when several leading countries simultaneously initiated huge, ambitious research programmes in the mid-2000s. Including the creation of new megascience projects – huge facilities that require thousands of people, cutting-edge technology, etc. In this world, we do not want just to hold the bar, but, as the presidential decree says, to become one of the world’s top five scientific powers in priority research directions.

— How do you define that? In terms of publications, it is the Higher School of Economics, which publishes a huge number of articles with a scientific value close to zero!

— I disagree with your thesis and assessment. Everything has to be measured and assessed correctly. The labour market and the reputation of the university are indicators. Competition for mathematics and physics at HSE is now one of the highest in the country, and HSE University graduates in these fields are almost the most demanded. In general, for a scientist, a researcher, the main product of his work is publications in internationally ranked journals, that means the most widely read ones. Is there any way to evaluate results differently?

— Is it possible to publish own journals instead of closing them down explaining it by a lack of funds?

— We have already started to support national scientific journals on a large scale last year, and this work will receive the most serious attention and continuation as part of the national Science project.

— You are the heirs of FASO…

— We are the successors of two federal bodies: the Ministry of Education and Science and the Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations. All the specialised departments and offices have become part of the new Ministry.

— For five years, FASO has actually carried out an inventory of the country’s scientific institutions. Reports were written, mountains of papers were sent from the country’s scientific institutions to the Agency. It’s all passed on to you now. Do you have a clear idea of what is good, what is bad in science, where we are ahead and what needs to be developed first?

— I do not agree that FASO existed only for inventory purposes, it was just one of the agency’s functions. And putting in order all the issues on federal property is a necessary process. I think you will not dispute the fact that a number of our scientific organizations have remained in the leading positions in Russia and the world. And in fact, all these restructurings have had little or no effect on many scientific organizations. Take the Institute of Nuclear Physics SB RAS, or the Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics in Chernogolovka, or the Institute of Applied Physics in Nizhniy Novgorod. I am simply giving examples from my field of science. They have made and are making money with intelligence.

I believe that one of the main results of the joint activities of FASO with the Academy and the Ministry of Education and Science has been the open evaluation of academic research organizations and the development of criteria for public expert evaluation. Prominent scientists such as Academicians V. A. Rubakov, A. R. Khokhlov, and many others worked in this commission. The evaluation was carried out. According to its results, only one-third of academic institutions fell into the first category and were judged to be the most efficient in science when compared to the global level. Then, there are about a third of organizations that perform their functions and have the potential to develop, but the topics do not always coincide with the priorities of the state scientific policy, the system of training and reproduction of the personnel is not always effective. So research is conducted, but it cannot be called cutting-edge. And about a third of the organizations is definitely in need of a qualitative transformation. And this is a normal process. In countries that have as much of a claim for scientific leadership in the world as we do – China, Japan, South Korea, India – there have been two or three waves of such fairly major transformations over the past 10 – 15 years. There have been major reforms of both national academies and scientific funding bodies.

— How about us?

— The economic conditions have changed a lot, so have the political ones. The Soviet Union was a power with a very different demographic trend and different infrastructural conditions. The world is changing very rapidly, and change is happening much faster now than it did 30 to 40 years ago.

— We have opened the doors to the world market and monsters have invaded and seized our wealth?

— We cannot be isolated from this market. So we need to perceive its laws, adapt the system intelligently, adjust and anticipate effective development mechanisms, not just think about the future, but try to implement it by creating opportunities, which is what the new Ministry plans to do. FASO did, I believe, set up a fairly sensible and open system of interaction with the Russian Academy of Sciences. The Scientific Coordinating Council (SCC) and the boards of directors of the institutes worked. A policy on personnel appointments was developed jointly with the Academy. Together with RAS and the Ministry of Education and Science, approaches were developed to prioritise thematic research plans. The process was sometimes painful, it was not easy to form a transparent system of decision-making and priorities, there were emotional discussions, but in my view, today the RAS institutions understand the system of coordinates in which they live and work.

— Universities are now getting active in science. Is this true, or is it just another illusion?

— In the 1990s and 2000s, there was a bias towards academic organizations – priority funding, support from the state. Undergraduate and postgraduate students went to research organizations. In the mid-2000s, the tendency changed fundamentally, the universities received close attention of the state and good funding, which gave greater impetus to their development. And this is now bearing fruit: Russian higher education is becoming increasingly competitive and attractive. Look at the rankings, today dozens of Russian universities are already in the prestigious cohorts. The number of international students choosing to study in Russia is growing. But the ship of science was rocked a little in the other direction. Now, in my opinion, the task of the new Ministry and the new national project is to form effective inter-institutional integration through balanced support and cooperation of academic organizations and universities.

Going back to the beginning of our conversation, intellectual resources are very scarce. There is now a huge struggle for brains and intelligence in various countries. What kind of programmes our friends and partners come up with! And funding is just one of the tools. There is a lot to offer, and both permitted and prohibited techniques are used.

And we have, I think, no other way than to make a common, unified system of scientific research. Scientific research should lose this connotation – university science and academic science. Research is common! Where it is more convenient and efficient to do them, where you can get results faster, there should be a certain transfer of resources and staff members. Universities, in my opinion, are a more dynamic system. Therefore, let us say, research projects with a shorter horizon and a greater chance of achieving a result can and should land in universities. More systematic, long-term, expensive research, where risks are higher and everything needs to be assessed even more responsibly, should be carried out in research institutes and sectoral R&D centres.

— I have the feeling that our science is somewhere in the past and that we have delayed its development. And now we begin to realise that this has to be changed very drastically, no matter what.

— Absolutely right. The world is changing extremely fast, and we have to not only react to changes, but also be ahead of some trends.

— What would you like to achieve as First Deputy Minister so that you can leave peacefully for the accelerator?

— I would like a few things. First of all, to create a frame of reference in which science and universities are not shaken too much by the constant reforms and transformations. That is, on the one hand, to establish certain vectors and directions of movement and, on the other hand, to give a certain freedom inside, so that the system does not have to be reconfigured every two or three years. I think this is one of the key things in the science area. This is probably the most difficult task. And education is even more inertial: the cycle of processes is seven or eight years, and it is the same with the horizon of expectation and evaluation of results. Higher education is slightly quicker, but using the most modern methods, it is still not possible to have a qualified specialist faster than in three to four years’ time. This is the primary task.

The second challenge relates to the support of scientists. We have so many different tools for individual researchers, teams, large teams, and projects, scientific organizations, and also for whole industries. Many of them came from different countries, having been carried over from there as a model.

Some emerged as a result of economic reforms, some initiatives from below or from the side. It would be good to streamline the system of these support measures so that it covers as widely as possible those who intend to enter science. It is important that the criteria are more universal and allow for the transfer of a scientist, team or project from one support mechanism to another. There should be no overlap and no mutually exclusive requirements, but rather a complementarity. And that there are no valleys of death that many of our academicians talk about. After all, what does that mean? We invest in the student, we prepare him or her. The person passed the USE well and entered university. He studies, the state pays for everything. He gets a scholarship, then grants. We lead him for up to 30 years and train him using state funds, we get a perfect specialist. And then his support disappears for five or seven years, for example. First, he is used to being cared about by the state, and second, he needs certain opportunities to keep up the level. Not finding them here, he goes abroad. That’s what needs to change. It is not an easy task, but it is manageable.

The third challenge is that we want a cooperation that works not under compulsion, but out of interest, where science produces not what it is interested in, but what is demanded by industry and the economy.

— This is applied science!

— Why? Some of the greats said that there is no such thing as fundamental or applied science. All basic science becomes applied science after some time, but the horizon is a year or 50 years. There are many examples of fundamental works from the 1960s and 1970s which are just now beginning to be used. Mankind knows where to apply the kinds of technologies it possesses today. And some development or technology has been lying in wait for 20 years. Therefore a two-way road has to be organized. In Soviet times, the institute had an implementation order and the industry had an acceptance order for these implementations. But this was largely formal.

— And everyone was happy!

— Everyone was formally accomplishing the task. But only there was no real alloy. And the problem is crucial: to get ahead and become one of the top five mentioned by the president, we need to solve it as quickly as possible. We live in an era of free economy and market. With elements of non-trivial global politics, of course. If you do something really necessary and useful, it will be in demand. Business imposes its own deadlines, its own laws. If it needs some technology tomorrow, they turn to the institute. And they say they need six months for this, six months for that, and maybe in a year and a half you will get a result. Businesses can’t wait, so they buy new things wherever they can get them done quicker.

— These are technological dreams, but a Russian person cannot do without a soul…

— The first three criteria I mentioned can be miscalculated. But there is another – the prestige of the profession. I want the attitude towards scientists to change and become what it was in the 1960s, at the time of S.P. Korolev and Y.A. Gagarin.

— What do you think is the biggest problem in the 21st century?

— I think the main objective is to preserve humanity. And then you can make different forecasts, examine the risks, the catastrophic trends – from the banal to the exotic ones.

— Aliens and other mischief?

— No, we are talking about a reboot that can happen. These are global trends in ecology and in digitalisation. We need to make sure that humans in the complex system of biological and technological organisms remain above artificial intelligence and various robotic systems. There are other dangers – climate change, resource depletion. Then there are all sorts of re-emerging infections and mutating viruses that we cannot manage with our medicine. The issue of preserving biodiversity on Earth exists. We think that man is the king of nature, but nature itself does not think so. I think a person has to keep at it all, to survive.

— Why did you take your children to the space park?

— Raising children is a very difficult task these days. You compete with sources of information. I just open a window to the world for my children and show them the possibilities. That’s how my parents brought me up. We have a very close-knit family. My mother opened books and took me to exhibitions and concerts. It was a cultural and educational component. And my father used to take me on trips all over the Union. He was a famous mountaineer, champion of the Soviet Union, the Snow Leopard. When I grew up, I chose my own path, using the accumulated baggage and life example of my parents. I want to pass the same on to the children. Not to push, but to show by example that everything can be achieved if you learn and work responsibly. The rest of the way is up to them anyway.

— What is Dubna to you?

— Dubna is a unique place, it’s always in my heart. There’s a painting on the wall in my office. I look at the endless Volga embankment, apple trees are in blossom. Dubna is certainly a big page in my life. I wouldn’t say this is the most important stage, because our family has lived in different places. Bratsk, where I was born, Lake Baikal, and Ukraine are equally important to me. I lived for a long time in Mykolaiv, in Odessa.

— And yet Dubna comes first?

— My children were born there and live there. I met my wife there and found a family. A few years of living in the dormitory have formed a circle of the brightest young people who came to Dubna from all over the country. They are now academic stars who have achieved success and recognition. In Dubna I made the decision for myself to pursue a career in science. I am a system engineer by education, having studied the design of information processing and management systems. I remember black and white computers and punch cards. I came to Dubna to study and gain experience, I was offered the job of automating a physics experiment. I didn’t understand physics as deeply as the institute required, but the environment was motivating and I wanted to learn and grow. The people I came into contact with were fantastic, my teachers and mentors, my elders. Terrific scientists and engineers, genuinely committed to science, willing to get involved with students. A wonderful strong research team, ambitious, versatile. My supervisor, Corresponding Member of the RAS I.N. Meshkov, still retains an amazing vitality. He has many students. He was involved in the world’s first colliders at Akademgorodok, Novosibirsk, and is now one of the leaders in the construction of the unique NICA Collider. He is the founder of the school of science in which I had the honour of being brought up. In general, I got into the right hands, in the right place, and at the right time, when major international projects were emerging in Dubna. And then I got into the NICA project with the light hand of A.N. Sissakian, an excellent scientist and organizer. In the last few years, my mentor was Academician V.A. Matveev, an outstanding theoretical physicist.

— Are there many such centres in our country?

— By definition, there can’t be many of them. Every country, even the leading one, has several. These are undoubtedly the Akademgorodok in Novosibirsk, Tomsk, the constellation of institutes around Moscow and St. Petersburg. An exceptional, growing, and ambitious Kurchatov Institute. The cities of Troitsk, Protvino are big science. There are other centres as well.

— Shall we go to discover the NICA Collider?

— Definitely.

— When?

— I go to rediscover it almost every weekend. You can see progress there every week, and not just in terms of the growing contours of the buildings and the collider tunnel, but also in terms of the equipment continually coming in. Now, by the way, one of the problems is the synchronisation of construction and assembly, testing, and installation of equipment. I hope to have the collider ring completed as early as 2020-2021. By this time, all the other elements of the huge complex will be ready. And then comes the most interesting part – the setting up of the machine and the first steps of a very complex experiment, the most long-awaited process that reveals to us the secrets of the universe.